- Home

- Rulfo, Juan

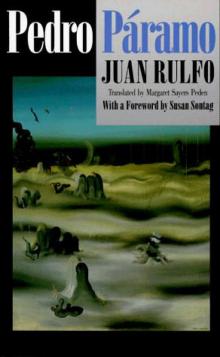

Pedro Paramo

Pedro Paramo Read online

Pedro Paramo

by

Juan Rulfo

I came to Comala because I had been told that my father, a man named Pedro Paramo lived there. It was my mother who told me. And I had promised her that after she died I would go see him. I squeezed her hands as a sign I would do it. She was near death, and I would have promised her anything. "Don't fail to go see him," she had insisted. "Some call him one thing, some another. I'm sure he will want to know you." At the time all I could do was tell her I would do what she asked, and from promising so often I kept repeating the promise even after I had pulled my hands free of her death grip.

Still earlier she had told me:

"Don't ask him for anything. Just what's ours. What he should have given me but never did. .

. . Make him pay, son, for all those years he put us out of his mind."

"I will, Mother."

I never meant to keep my promise. But before I knew it my head began to swim with dreams and my imagination took flight. Little by little I began to build a world around a hope centered on the man called Pedro Paramo, the man who had been my mother's husband. That was why I had come to Comala.

It was during the dog days, the season when the August wind blows hot, venomous with the rotten stench of saponaria blossoms.

The road rose and fell. It rises or falls depending on whether you're coming or going. If you are leaving, it's uphill; but as you arrive it's downhill.

"What did you say that town down there is called?"

"Comala, senor."

"You're sure that's Comala?"

"I'm sure, senor."

"It's a sorry-looking place, what happened to it?"

"It's the times, senor."

I had expected to see the town of my mother's memories, of her nostalgia - nostalgia laced with sighs. She had lived her lifetime sighing about Comala, about going back. But she never had. Now I had come in her place. I was seeing things through her eyes, as she had seen them. She had given me her eyes to see. Just as you pass the gate of Los Colimotes there's a beautiful view of a green plain tinged with the yellow of ripe corn. From there you can see Comala, turning the earth white, and lighting it at night. Her voice was secret, muffled, as if she were talking to herself. . . . Mother.

"And why are you going to Comala, if you don't mind my asking?" I heard the man say.

"I've come to see my father," I replied.

"Umh!" he said.

And again silence.

We were making our way down the hill to the clip-clop of the burros' hooves. Their sleepy eyes were bulging from the August heat.

"You're going to get some welcome." Again I heard the voice of the man walking at my side. "They'll be happy to see someone after all the years no one's come this way."

After a while he added: "Whoever you are, they'll be glad to see you."

In the shimmering sunlight the plain was a transparent lake dissolving in mists that veiled a gray horizon. Farther in the distance, a range of mountains. And farther still, faint remoteness.

"And what does your father look like, if you don't mind my asking?"

"I never knew him," I told the man. "I only know his name is Pedro Paramo."

"Umh! that so?"

"Yes. At least that was the name I was told."

Yet again I heard the burro driver's "Umh!"

I had run into him at the crossroads called Los Encuentros. I had been waiting there, and finally this man had appeared.

"Where are you going?" I asked.

"Down that way, senor."

"Do you know a place called Comala?"

"That's the very way I'm going."

So I followed him. I walked along behind, trying to keep up with him, until he seemed to remember I was following and slowed down a little. After that, we walked side by side, so close our shoulders were nearly touching.

"Pedro Paramo's my father, too," he said.

A flock of crows swept across the empty sky, shrilling "caw, caw, caw."

Up-and downhill we went, but always descending. We had left the hot wind behind and were sinking into pure, airless heat. The stillness seemed to be waiting for something.

"It's hot here," I said.

"You might say. But this is nothing," my companion replied. "Try to take it easy. You'll feel it even more when we get to Comala. That town sits on the coals of the earth, at the very mouth of hell. They say that when people from there die and go to hell, they come back for a blanket."

"Do you know Pedro Paramo?" I asked.

I felt I could ask because I had seen a glimmer of goodwill in his eyes.

"Who is he?" I pressed him.

"Living bile," was his reply.

And he lowered his stick against the burros for no reason at all, because they had been far ahead of us, guided by the descending trail.

The picture of my mother I was carrying in my pocket felt hot against my heart, as if she herself were sweating. It was an old photograph, worn around the edges, but it was the only one I had ever seen of her. I had found it in the kitchen safe, inside a clay pot filled with herbs: dried lemon balm, castilla blossoms, sprigs of rue. I had kept it with me ever since.

It was all I had. My mother always hated having her picture taken. She said photographs were a tool of witchcraft. And that may have been so, because hers was riddled with pinpricks, and at the location of the heart there was a hole you could stick your middle finger through.

I had brought the photograph with me, thinking it might help my father recognize who I was.

"Take a look," the burro driver said, stopping. "You see that rounded hill that looks like a hog bladder? Well, the Media Luna lies right behind there. Now turn that way. You see the brow of that hill? Look hard. And now back this way. You see that ridge? The one so far you can't hardly see it? Well, all that's the Media Luna.

From end to end. Like they say, as far as the eye can see. He owns ever" bit of that land.

We're Pedro Paramo's sons, all right, but, for all that, our mothers brought us into the world on straw mats. And the real joke of it is that he's the one carried us to be baptized. That's how it was with you, wasn't it?"

"I don't remember."

"The hell you say!"

"What did you say?"

"I said, we're getting there, senor."

"Yes. I see it now. . . . What could it have been?"

"That was a correcaminos, senor. A roadrunner. That's what they call those birds around here."

"No. I meant I wonder what could have happened to the town? It looks so deserted, abandoned really. In fact, it looks like no one lives here at all."

"It doesn't just look like no one lives here. No one does live here."

"And Pedro Paramo?"

"Pedro Paramo died years ago."

It was the hour of the day when in every little village children come out to play in the streets, filling the afternoon with their cries. The time when dark walls still reflect pale yellow sunlight.

At least that was what I had seen in Sayula, just yesterday at this hour. I'd seen the still air shattered by the flight of doves flapping their wings as if pulling themselves free of the day.

They swooped and plummeted above the tile rooftops, while the children's screams whirled and seemed to turn blue in the dusk sky.

Now here I was in this hushed town.Tcould hear my footsteps on the cobbled paving stones. Hollow footsteps, echoing against walls stained red by the setting sun.

This was the hour I found myself walking down the main street.

Nothing but abandoned houses, their empty doorways overgrown with weeds. What had the stranger told me they were called? "La gobernadora, senor. Creosote bush. A plague that takes over a person's house the minute he leaves. You'll see."

As I passed a street corner, I saw a woman wrapped in her rebozo; she disappeared as if she had never existed. I started forward again, peering into the doorless houses. Again the woman in the rebozo crossed in front of me.

"Evening," she said.

I looked after her. I shouted: "Where will I find dona Eduviges?"

She pointed: "There. The house beside the bridge."

I took note that her voice had human overtones, that her mouth was filled with teeth and a tongue that worked as she spoke, and that her eyes were the eyes of people who inhabit the earth.

By now it was dark.

She turned to call good night. And though there were no children playing, no doves, no blue-shadowed roof tiles, I felt that the town was alive. And that if I heard only silence, it was because I was not yet accustomed to silence - maybe because my head was still filled with sounds and voices.

Yes, voices. And here, where the air was so rare, I heard them even stronger. They lay heavy inside me. I remembered what my mother had said: "You will hear me better there. I will be closer to you. You will hear the voice of my memories stronger than the voice of my death - that is, if death ever had a voice." Mother. . . . So alive.

How I wished she were here, so I could say, "You were mistaken about the house. You told me the wrong place. You sent me 'south of nowhere,' to an abandoned village. Looking for someone who's no longer alive."

I found the house by the bridge by following the sound of the river. I lifted my hand to knock, but there was nothing there. My hand met only empty space, as if the wind had blown open the door. A woman stood there. She said, "Come in." And I went in.

So I stayed in Comala. The man with the burros had gone on his way. Before leaving, he'd said:

"I still have a way to go, yonder where you see that band of hills. My house is there. If you want to come, you will be welcome. For now, if you want to stay here, then stay. You got nothing to lose by taking a look around, you may find someone who's still among the living."

I stayed. That was why I had come.

"Where can I find lodging?" I called, almost shouting now.

"Look up dona Eduviges, if she's still alive. Tell her I sent you."

"And what's your name?"

'Abundio," He called back. But he was too far for me to hear his last name.

I am Eduviges Dyada. Come in."

It was as if she had been waiting for me. Everything was ready, she said, motioning for me to follow her through a long series of dark, seemingly empty, rooms. But no. As soon as my eyes grew used to the darkness and the thin thread of light following us, I saw shadows looming on either side, and sensed that we were walking down a narrow passageway opened between bulky shapes.

"What do you have here?" I asked.

"Odds and ends," she said. "My house is chock full of other people's things. As people went away, they chose my house to store their belongings, but not one of them has ever come back to claim them. The room I kept for you is here at the back. I keep it cleaned out in case anyone comes. So you're her son?"

"Whose son?" I asked.

"Doloritas's boy."

"Yes. But how did you know?"

"She told me you would be coming. Today, in fact. That you would be coming today."

"Who told you? My mother?"

"Yes. Your mother."

I did not know what to think. But Eduviges left me no time for thinking.

"This is your room," she said.

The room had no doors, except for the one we had entered. She lighted the candle, and I could see the room was completely empty.

"There's no place to sleep," I said.

"Don't worry about that. You must be tired from your journey, and weariness makes a good mattress. I'll fix you up a bed first thing in the morning. You can't expect me to have things ready on the spur of the moment. A person needs some warning, and I didn't get word from your mother until just now."

"My mother?" I said. "My mother is dead."

"So that was why her voice sounded so weak, like it had to travel a long distance to get here.

Now I understand. And when did she die?"

"A week ago."

"Poor woman. She must've thought I'd forsaken her. We made each other a promise we'd die together. That we would go hand in hand, to lend each other courage on our last journey - in case we had need for something, or ran into trouble. We were the best of friends. Didn't she ever talk about me?"

"No, never."

"That's strange. Of course, we were just girls then. She was barely married. But we loved each other very much. Your mother was so pretty, so, well, sweet, that it made a person happy to love her. You wanted to love her. So, she got a head start on me, eh? Well, you can be sure I'll catch up with her. No one knows better than I do how far heaven is, but I also know all the shortcuts. The secret is to die, God willing, when you want to, and not when He proposes. Or else to force Him to take you before your time. Forgive me for going on like this, talking to you as if we were old friends, but I do it because you're like my own son. Yes, I said it a thousand times: 'Dolores's boy should have been my son.' I'll tell you why sometime. All I want to say now is that I'll catch up with your mother along one of the roads to eternity."

I wondered if she were crazy. But by now I wasn't thinking at all. I felt I was in a faraway world and let myself be pulled along by the current. My body, which felt weaker and weaker, surrendered completely; it had slipped its ties and anyone who wanted could have wrung me out like a rag.

"I'm tired," I said.

"Come eat something before you sleep. A bite. Anything there is."

"I will. I'll come later."

Water dripping from the roof tiles was forming a hole in the sand of the patio. Plink! plink! and then another plink! as drops struck a bobbing, dancing laurel leaf caught in a crack between the adobe bricks. The storm had passed. Now an intermittent breeze shook the branches of the pomegranate tree, loosing showers of heavy rain, spattering the ground with gleaming drops that dulled as they sank into the earth. The hens, still huddled on their roost, suddenly flapped their wings and strutted out to the patio, heads bobbing, pecking worms unearthed by the rain. As the clouds retreated the sun flashed on the rocks, spread an iridescent sheen, sucked water from the soil, shone on sparkling leaves stirred by the breeze.

"What's taking you so long in the privy, son?"

"Nothing, mama."

"If you stay in there much longer, a snake will come and bite you."

"Yes, mama."

I was thinking of you, Susana of the green hills. Of when we used to fly kites in the windy season. We could hear the sounds of life from the town below; we were high above on the hill, playing out string to the wind. "Help me, Susana." And soft hands would tighten on mine. "Let out more string."

The wind made us laugh; our eyes followed the string running through our fingers after the wind until with a faint pop! it broke, as if it had been snapped by the wings of a bird.

And high overhead, the paper bird would tumble and somersault, trailing its rag tail, until it disappeared into the green earth.

Your lips were moist, as if kissed by the dew.

"I told you, son, come out of the privy now."

"Yes, mama. I'm coming."

I was thinking of you. Of the times you were there looking at me with your aquamarine eyes.

He looked up and saw his mother in the doorway.

"What's taking you so long? What are you doing in there?"

"I'm thinking."

"Can't you do it somewhere else? It's not good for you to stay in the privy so long.

Besides, you should be doing something. Why don't you go help your grandmother shell corn?"

"I'm going, mama. I'm going."

Grandmother, I've come to help you shell corn."

"We're through with that, but we still have to grind the chocolate. Where have you been?

We were looking for you all during the storm."

"I was in the b

ack patio." "And what were you doing? Praying?" "No, Grandmother. I was just watching it rain." His grandmother looked at him with those yellow-gray eyes that seemed to see right through a person. "Run clean the mill, then."

Hundreds of meters above the clouds, far, far above everything, you are hiding, Susana.

Hiding in God's immensity, behind His Divine Providence where I cannot touch you or see you, and where my words cannot reach you.

"Grandmother, the mill's no good. The grinder's broken." "That Micaela must have run corn through it. I can't break her of that habit, but it's too late now."

"Why don't we buy a new one? This one's so old it isn't any good anyway."

"That's the Lord's truth. But with all the money we spent to bury your grandfather, and the tithes we've paid to the church, we don't have anything left. Oh, well, we'll do without something else and buy a new one. Why don't you run see dona Ines Villalpando and ask her to carry us on her books until October. We'll pay her at harvest time."

"All right, Grandmother."

"And while you're at it, to kill two birds with one stone, ask her to lend us a sifter and some clippers. The way those weeds are growing, well soon have them coming out our ears. If I had my big house with all my stock pens, I wouldn't be complaining. But your grandfather took care of that when he moved here. Well, it must be God's will. Things seldom work out the way you want. Tell dona Ines that after harvest time we'll pay her everything we owe her."

"Yes, Grandmother."

Hummingbirds. It was the season. He heard the whirring of their wings in blossom-heavy jasmine.

He stopped by the shelf where the picture of the Sacred Heart stood, and found twenty-four centavos. He left the four single coins and took the veinte.

As he was leaving, his mother stopped him:

"Where are you going?"

"Down to dona Ines Villalpando's, to buy a new mill. Ours broke."

"Ask her to give you a meter of black taffeta, like this," and she handed him a piece.

"And to put it on our account."

"All right, mama."

"And on the way back, buy me some aspirin. You'll find some money in the flowerpot in the hall."

He found a peso. He left the veinte and took the larger coin. "Now I have enough money for anything that comes along," he thought.

Pedro Paramo

Pedro Paramo