- Home

- Rulfo, Juan

Pedro Paramo Page 2

Pedro Paramo Read online

Page 2

"Pedro!" people called to him. "Hey, Pedro!"

But he did not hear. He was far, far away.

During the night it began to rain again. For a long time, he lay listening to the gurgling of the water; then he must have slept, because when he awoke, he heard only a quiet drizzle. The windowpanes were misted over and raindrops were threading down like tears.

. . . I watched the trickles glinting in the lightning flashes, and every breath I breathed, I sighed. And every thought I thought was of you, Susana.

The rain turned to wind. He heard " . . . the forgiveness of sins and the resurrection of the flesh. Amen." That was deeper in the house, where women were telling the last of their beads. They got up from their prayers, they penned up the chickens, they bolted the door, they turned out the light.

Now there was only the light of night, and rain hissing like the murmur of crickets.

"Why didn't you come say your Rosary? We were making a novena for your grandfather."

His mother was standing in the doorway, candle in hand. Her long, crooked shadow stretched toward the ceiling. The roof beams repeated it, in fragments.

"I feel sad," he said.

Then she turned away. She snuffed out the candle. As she closed the door, her sobs began; he could hear them for a long time, mixed with the sound of the rain.

The church clock tolled the hours, hour after hour, hour after hour, as if time had been telescoped.

Oh, yes. I was nearly your mother. She never told you anything about it?"

"No. She only told me good things. I heard about you from the man with the train of burros. The man who led me here, the one named Abundio."

"He's a good man, Abundio. So, he still remembers me? I used to give him a little something for every traveler he sent to my house. It was a good deal for both of us. Now, sad to say, times have changed, and since the town has fallen on bad times, no one brings us any news. So he told you to come see me?"

"Yes, he said to look for you."

"I'm grateful to him for that. He was a good man, one you could trust. It was him that brought the mail, and he kept right on even after he went deaf. I remember the black day it happened. Everyone felt bad about it, because we all liked him. He brought letters to us and took ours away. He always told us how things were going on the other side of the world, and doubtless he told them how we were making out. He was a big talker. Well, not afterward.

He stopped talking then. He said there wasn't much point in saying things he couldn't hear, things that evaporated in the air, things he couldn't get the taste of. It all happened when one of those big rockets we use to scare away water snakes went off too close to his head.

From that day on, he never spoke, though he wasn't struck dumb. But one thing I tell you, it didn't make him any less a good person."

"The man I'm talking about heard fine."

"Then it can't have been him. Besides, Abundio died. I'm sure he's dead. So you see? It couldn't have been him."

"I guess you're right."

"Well, getting back to your mother. As I was telling you . . . "

As I listened to her drone on, I studied the woman before me. I thought she must have gone through some bad times. Her face was transparent, as if the blood had drained from it, and her hands were all shriveled, nothing but wrinkled claws. Her eyes were sunk out of sight. She was wearing an old-fashioned white dress with rows of ruffles, and around her neck, strung on a cord, she wore a medal of the Maria Santisima del Refugio with the words "Refuge of Sinners."

". . . This man I'm telling you about broke horses over at the Media Luna ranch; he said his name was Inocencio Osorio. Everyone knew him, though, by his nickname 'Cockleburr'; he could stick to a horse like a burr to a blanket. My compadre Pedro used to say that the man was born to break colts. The fact is, though, that he had another calling: conjuring. He conjured up dreams. That was who he really was. And he put it over on your mother, like he did so many others. Including me. Once when I was feeling bad, he showed up and said, 'I've come to give you a treatment so's you'll feel better.' And what that meant was he would start out kneading and rubbing you: first your fingertips, then he'd stroke your hands, then your arms. First thing you knew he'd be working on your legs, rubbing hard, and soon you'd be feeling warm all over. And all the time he was rubbing and stroking he'd be telling you your fortune. He would fall into a trance and roll his eyes and conjure and curse, with spittle flying everywhere - you'd of thought he was a gypsy.

Sometimes he would end up stark naked; he said we wanted it that way. And sometimes what he said came true. He shot at so many targets that once in a while he was bound to hit one.

"So what happened was that when your mother went to see this Osorio, he told her that she shouldn't lie with a man that night because the moon was wrong.

"Dolores came and told me everything, in a quandary about what to do. She said there was no two ways about it, she couldn't go to bed with Pedro Paramo that night. Her wedding night. And there I was, trying to convince her she shouldn't put any stock in that Osorio, who was nothing but a swindler and a liar.

"'I can't,' she told me. 'You go for me. He'll never catch on.'

"Of course I was a lot younger than she was. And not quite as dark-skinned. But you can't tell that in the dark.

"'It'll never work, Dolores. You have to go.'

'"Do me this one favor, and I'll pay you back a hundred times over.'

"In those days your mother had the shyest eyes. If there was something pretty about your mother, it was those eyes. They could really win you over.

'"You go in my place,' she kept saying.

"So I went.

"I took courage from the darkness, and from something else your mother didn't know, and that was that she wasn't the only one who liked Pedro Paramo.

"I crawled in bed with him. I was happy to; I wanted to. I cuddled right up against him, but all the celebrating had worn him out and he spent the whole night snoring. All he did was wedge his legs between mine.

"Before dawn, I got up and went to Dolores. I said to her: 'You go now. It's a new day.'

'"What did he do to you?' she asked me.

"'I'm still not sure,' I told her.

"You were born the next year, but I wasn't your mother, though you came within a hair of being mine.

"Maybe your mother was ashamed to tell you about it."

Green pastures. Watching the horizon rise and fall as the wind swirled through the wheat, an afternoon rippling with curling lines of rain. The color of the earth, the smell of alfalfa and bread. A town that smelled like spilled honey . . .

"She always hated Pedro Paramo. 'Doloritas! Did you tell them to get my breakfast?'

Your mother was up every morning before dawn. She would start the fire from the coals, and with the smell of the tinder the cats would wake up. Back and forth through the house, followed by her guard of cats. 'Dona Doloritas!'

"I wonder how many times your mother heard that call? 'Dona Doloritas, this is cold. It won't do.' How many times? And even though she was used to the worst of times, those shy eyes of hers grew hard."

Not to know any taste but the savor of orange blossoms in the warmth of summer.

"Then she began her sighing.

'"Why are you sighing so, Doloritas?'

"I had gone with them that afternoon. We were in the middle of a field, watching the bevies of young thrushes. One solitary buzzard rocked lazily in the sky.

'"Why are you sighing, Doloritas?'

'"I wish I were a buzzard so I could fly to where my sister lives.'

"That's the last straw, dona Doloritas!' You'll see your sister, all right. Right now. We're going back to the house and you're going to pack your suitcases. That was the last straw!'

"And your mother went. Til see you soon, don Pedro.'

"'Good-bye, Doloritas!'

"And she never came back to the Media Luna. Some months later, I asked Pedro Paramo about her.

'"She love

d her sister more than she did me. I guess she's happy there. Besides, I was getting fed up with her. I have no intention of asking about her, if that's what's worrying you.'

'"But how will they get along?'

"'Let God look after them.'"

. . . Make him pay, Son, for all those year she put us out of his mind.

"And that's how it was until she advised me that you were coming to see me. We never heard from her again."

"A lot has happened since then," I told Eduviges. "We lived in Colima. We were taken in by my Aunt Gertrudis, who threw it in our faces every day that we were a burden. She used to ask my mother, 'Why don't you go back to your husband?'

'"Oh? Has he sent for me? I'm not going back unless he asks me to. I came because I wanted to see you. Because I loved you. That's why I came.'

'"I know that. But it's time now for you to leave.'

"'If it was up to me . . .'"

I thought that Eduviges was listening to me. I noticed, though, that her head was tilted as if she were listening to some faraway sound. Then she said:

“When will you rest?"

The day you went away I knew I would never see you again. You were stained red by the late afternoon sun, by the dusk filling the sky with blood. You were smiling. You had often said of the town you were leaving behind, "I like it because of you; but I hate everything else about it - even having been born here." I thought, she will never come back; I will never see her again.

"What are you doing here at this hour? Aren't you working?"

"No, Grandmother. Rogelio asked me to mind his little boy. I'm just walking him around.

I can't do both things - the kid and the telegraph. Meanwhile he's down at the poolroom drinking beer. On top of everything else, he doesn't pay me anything."

"You're not there to be paid. You're there to learn. Once you know something, then you can afford to make demands. For now, you're just an apprentice. Maybe one day you will be the boss. But for that you need patience and, above all, humility. If they want you to take the boy for a walk, do it, for heaven's sake. You must learn to be patient."

"Let others be patient, Grandmother. I'm not one for patience."

"You and your wild ideas! I'm afraid you have a hard row ahead of you, Pedro Paramo."

What was that I just heard, dona Eduviges?"

She shook her head as if waking from a dream.

"That’s Miguel Paramo's horse, galloping down the road to the Media Luna"?"

"Then someone's living there?"

"No, no one's living there."

"But. . .?"

"It's only his horse, coming and going. They were never apart. It roams the countryside, looking for him, and it's always about this time it comes back. It may be that the poor creature can't live with its remorse. Even animals realize when they've done something bad, don't they?"

"I don't understand. I didn't hear anything that sounded like a horse."

"No?"

"No."

"Then it must be my sixth sense. A gift God gave me — or maybe a curse. All I know is that I've suffered because of it."

She said nothing for a while, but then added:

"It all began with Miguel Paramo. I was the only one knew everything that happened the night he died. I'd already gone to bed when I heard his horse galloping back toward the Media Luna. I was surprised, because Miguel never came home at that hour. It was always early morning before he got back. He went every night to be with his sweetheart over in a town called Contla, a good distance from here. He left early and got back late. But that night he never returned. . . . You hear it now? Of course you can hear it. It's his horse coming home."

"I don't hear anything."

"Then it's just me. Well, like I was saying, the fact that he didn't come back wasn't the whole story. His horse had no more than gone by when I heard someone rapping at my window. Now you be the judge of whether it was my imagination. What I know is that something made me get up and go see who it was. And it was him. Miguel Paramo. I wasn't surprised to see him, because there was once a time when he spent every night at my house, sleeping with me — until he met that girl who drank his blood.

'"What's happened,' I asked Miguel Paramo. 'Did she give you the gate?'

'"No. She still loves me,' he said. The problem is that I couldn't locate her. I couldn't find my way to the town. There was a lot of mist or smoke or something. I do know that Contla isn't there anymore. I rode right past where it ought to be, according to my calculations, and there was nothing there. I've come to tell you about it, because I know you will understand. If I told anyone else in Comala they'd say I'm crazy - the way they always have.'

'"No. Not crazy, Miguel. You must be dead. Remember, everyone told you that horse would be the death of you one day. Remember that, Miguel Paramo. Maybe you did do something crazy, but that's another matter now.'

"'All I did was jump that new stone fence my father had built. I asked El Colorado to jump it so I wouldn't have to go all the way around, the way you have to now to get to the road. I know that I jumped it, and then kept on riding. But like I told you, everything was smoke, smoke, smoke.'

'"Your father's going to be sick with grief in the morning,' I told him. 'I feel sorry for him.

Now go, and rest in peace, Miguel. I thank you for coming to say good-bye.'

"And I closed the window. Before dawn, a ranch hand from the Media Luna came to tell me, 'The patron is asking for you. Young Miguel is dead. Don Pedro wants your company.'

'"I already knew,' I told him. 'Did they tell you to cry?' "'Yes. Don Fulgor told me to cry when I told you.' '"All right. You tell don Pedro that I'll be there. How long ago did they bring him back?'

'"No more than half an hour. If it'd been sooner, maybe they could of saved him.

Although the doctor who looked him over said he had been cold for some time. We learned about it when El Colorado came home with an empty saddle and made such a stir that no one could sleep. You know how him and that horse loved one another, and as for me, I think the animal is suffering more than don Pedro. He hasn't eaten or slept, and all he does is chase around in circles. Like he knows, you know? Like he feels all broken and chewed up inside.'

'"Don't forget to close the door as you go.'

"And with that the hand from the Media Luna left."

"Have you ever heard the moan of a dead man?" she asked me.

"No, dona Eduviges."

"You're lucky."

Drops are falling steadily on the stone trough. The air carries the sound of the clear water escaping the stone and falling into the storage urn. He is conscious of sounds: feet scraping the ground, back and forth, back and forth. The endless dripping. The urn overflows, spilling water onto the wet earth.

"Wake up," someone is saying.

He hears the sound of the voice. He tries to identify it, but he sinks back down and drowses again, crushed by the weight of sleep. Hands tug at the covers; he snuggles beneath their warmth, seeking peace.

"Wake up!" Again someone is calling.

That someone is shaking his shoulders. Making him sit up. He half opens his eyes. Again he hears the dripping of water falling from the stone into the brimming urn. And those shuffling footsteps . . . And weeping.

Then he heard the weeping. That was what woke him: a soft but penetrating weeping that because it was so delicate was able to slip through the mesh of sleep and reach the place where his fear lived.

Slowly he got out of bed; he saw a woman's face resting against a doorframe still darkened by night. The woman was sobbing.

"Why are you crying, mama?" he asked; the minute his feet touched the floor he recognized his mother's face.

"Your father is dead," she said.

And then, as if her coiled grief had suddenly burst free, she turned and turned in a tight circle until hands grasped her shoulders and stopped the spiraling of her tortured body.

Through the door he could see the dawn. There were no stars. Only a leaden

gray sky still untouched by the rays of the sun. A drab light that seemed more like the onset of night than the beginning of day.

Outside in the patio, the footsteps, like people wandering in circles. Muted sounds. And inside, the woman standing in the doorway, her body impeding the arrival of day: through her arms he glimpsed pieces of sky and, beneath her feet, trickles of light. A damp light, as if the floor beneath the woman were flooded with tears. And then the sobbing. Again the soft but penetrating weeping, and the grief contorting her body with pain.

"They've killed your father."

And you, Mother? Who killed you?

There is wind and sun, and there are clouds. High above, blue sky, and beyond that there may be songs; perhaps sweeter voices. . . . In a word, hope. There is hope for us, hope to ease our sorrows.

"But not for you, Miguel Paramo, for you died without forgiveness and you will never know God's grace."

Father Renteria walked around the corpse, reciting the mass for the dead. He hurried in order to finish quickly, and he left without offering the final benediction to the people who filled the church.

"Father, we want you to bless him!"

"No," he said, shaking his head emphatically. "I won't give my blessing. He was an evil man, and he shall not enter the Kingdom of Heaven. God will not smile on me if I intercede for him."

As he spoke, he clasped his hands tightly, hoping to conceal their trembling. To no avail.

That corpse weighed heavily on the soul of everyone present. It lay on a dais in the Center of the church, surrounded with new candles and flowers; a father stood there, alone, waiting for the mass to end.

Father Renteria walked past Pedro Paramo, trying not to brush against him. He raised the aspergillum gently, sprinkling holy water from the top of the coffin to the bottom, while a murmur issued from his lips that might have been a prayer. Then he knelt, and everyone knelt with him:

"Oh, God, have mercy on this Your servant."

"May he rest in peace, Amen," the voices chorused.

Then, as his rage was building anew, he saw that everyone was leaving the church, and that they were carrying out the body of Miguel Paramo.

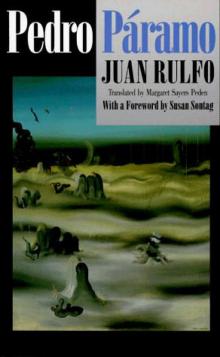

Pedro Paramo

Pedro Paramo