- Home

- Rulfo, Juan

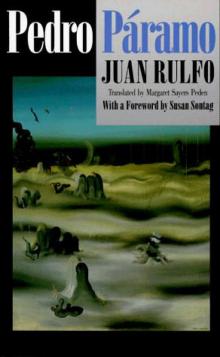

Pedro Paramo Page 3

Pedro Paramo Read online

Page 3

Pedro Paramo approached him and knelt beside him:

"I know you hated him, Father. And with reason. Rumor has it that your brother was murdered by my son, and you believe that your niece Ana was raped by him. Then there were his insults, and his lack of respect. Those are all reasons anyone could understand.

But forget all that now, Father. Weigh him and forgive him, as perhaps God has forgiven him."

He placed a handful of gold coins on the prie-dieu and got to his feet: "Take this as a gift for your church."

The church was empty now. Two men stood in the doorway, waiting for Pedro Paramo.

He joined them, and together they followed the coffin that had been waiting for them, resting on the shoulders of four foremen from the Media Luna. Father Renteria picked up the coins, one by one, and walked to the altar.

"These are Yours," he said. "He can afford to buy salvation. Only you know whether this is the price. As for me, Lord, I throw myself at your feet to ask for the justice or injustice that any of us may ask . . . For my part, I hope you damn him to hell."

And he closed the chapel.

He walked to the sacristy, threw himself into a corner, and sat there weeping with grief and sorrow until his tears were exhausted.

"All right, Lord. You win," he said.

At suppertime, he drank his hot chocolate as he did every night. He felt calm.

"So, Anita. Do you know who was buried today?"

"No, Uncle."

"You remember Miguel Paramo?"

"Yes, Uncle."

"Well, that's who."

Ana hung her head.

"You are sure he was the one, aren't you?"

"I'm not positive, Uncle. No. I never saw his face. He surprised me at night, and it was dark."

"Then how did you know it was Miguel Paramo?"

"Because he said so: 'It's Miguel Paramo, Ana. Don't be afraid.' That was what he said."

"But you knew he was responsible for your father's death, didn't you?"

"Yes, Uncle."

"So what did you do to make him leave?"

"I didn't do anything."

The two sat without speaking. They could hear the warm breeze stirring in the myrtle leaves.

"He said that was why he had come: to say he was sorry and to ask me to forgive him. I lay still in my bed, and I told him, The window is open.' And he came in. The first thing he did was put his arms around me, as if that was his way of asking forgiveness for what he had done. And I smiled at him. I remembered what you had taught me: that we must never hate anyone. I smiled to let him know that, but then I realized that he couldn't see my smile because it was so black that I couldn't see him. I could only feel his body on top of me, and feel him beginning to do bad things to me.

"I thought he was going to kill me. That's what I believed, Uncle. Then I stopped thinking at all, so I would be dead before he killed me. But I guess he didn't dare.

"I knew he hadn't when I opened my eyes and saw the morning light shining in the open window. Up till then, I felt that I had in fact died."

"But you must have some way of being sure. His voice. Didn't you recognize him by his voice?"

"I didn't recognize him at all. All I knew about him was that he had killed my father. I had never seen him, and afterward I never saw him again. I couldn't have faced him, Uncle."

"But you knew who he was."

"Yes. And what he was. And I know that by now he must be in the deepest pit of hell. I prayed to all the saints with all my heart and soul."

"Don't be too sure of that, my child. Who knows how many people are praying for him! You are alone. One prayer against thousands. And among them, some much more intense than yours — like his father's."

He was about to say: "And anyway, I have pardoned him." But he only thought it. He did not want to add hurt to the girl's already broken spirit. Instead, he took her arm and said: "Let us give thanks to the Lord our God, Who has taken him from this earth where he caused such harm; what does it matter if He lifted him to His heaven?"

A horse galloped by the place where the main street crosses the road to Contla. No one saw it. Nevertheless, a woman waiting on the outskirts of the village told that she had seen the horse, and that its front legs were buckled as if about to roll head over hooves. She recognized it as Miguel Paramo's chestnut stallion. The thought had even crossed her mind that the animal was going to break its neck. Then she saw it regain its footing and without any interruption in stride race off with its head twisted back, as if frightened by something it had left behind.

That story reached the Media Luna on the night of the burial, as the men were resting after the long walk back from the cemetery.

They were talking, as people talk everywhere before turning in.

"That death pained me in more ways than one," said Terencio Lubianes. "My shoulders are still sore."

"Mine, too," said his brother Ubillado. "And my bunions must have swelled an inch. All because the patron wanted us to wear shoes. You'd have thought it was a holy day, right, Toribio?"

"What do you want me to say? I think it was none too soon he died."

In a few days there was more news from Contla. It came with the latest ox cart.

"They're saying that his spirit is wandering over there. They've seen it rapping at the window of a lady friend. It was just like him. Chaps and all."

"And do you think that don Pedro, with that disposition of his, would allow his son to keep calling on the women? I can just imagine what he'd say if he found out: All right,' he'd say.

'You're dead now. You keep to your grave. And leave the affairs to us.' And if he caught him wandering around, you can bet he'd put him back in the ground for good."

"You're right about that, Isaias. That old man doesn't put up with much."

The driver went on his way. "I'm just telling you what was told me."

Shooting stars. They fell as if the sky were raining fire.

"Look at that," said Terencio. "Please look at the show they're putting on up there."

"Must be celebrating Miguelito's arrival," Jesus put in.

You don't think it's a bad omen?"

"Bad for who?"

"Maybe your sister's lonesome and wants him back."

"Who're you talking to?"

"To you."

"It's time to go, boys. We've traveled a long road today, and we have to be up early tomorrow."

And they faded into the night like shadows.

Shooting stars. One by one, the lights in Comala went out.

Then the sky took over the night.

Father Renteria tossed and turned in his bed, unable to sleep.

It's all my fault, he told himself. Everything that's happening. Because I'm afraid to offend the people who provide for me. It's true; I owe them my livelihood. I get nothing from the poor, and God knows prayers don't fill a stomach. That's how it's been up to now.

And we're seeing the consequences. All my fault. I have betrayed those who love me and who have put their faith in me and come to me to intercede on their behalf with God.

What has their faith won them? Heaven? Or the purification of their souls? And why purify their souls anyway, when at the last moment. . . I will never forget Maria Dyada's face when she came to ask me to save her sister Eduviges:

She always served her fellowman. She gave them everything she had. She even gave them sons. All of them. And took the infants to their fathers to be recognized. But none of them wanted to. Then she told them, 'In that case, I'll be the father as well, even though fate chose me to be the mother.' Everyone took advantage of her hospitality and her good nature; she never wanted to offend, or set anyone against her."

“She took her own life. She acted against the will of God."

"She had no choice. That was another thing she did out of the goodness of her heart."

"She fell short at the last hour," that's what I told Maria Dyada.

"At the last minute. So many good acts stored up

for her salvation, and then to lose them like that, all at once!"

"But she didn't lose them. She died of her sorrows. And sorrow . . . You once told us something about sorrow that I can't remember now. It was because of her sorrows she went away. And died choking on her own blood. I can still see how she looked. That face was the saddest face I have ever seen on a human."

"Perhaps with many prayers . . . "

"We're already saying many prayers, Father."

"I mean maybe, just perhaps, with Gregorian masses. But for that we would need help, have to bring priests here. And that costs money."

And there before my eyes was the face of Maria Dyada, a poor woman still ripe with children.

"I don't have money. You know that, Father."

"Let's leave things as they are. Let us put our hope in God."

"Yes, Father."

Why did she look courageous in her resignation? And what would it have cost him to grant pardon when it was so easy to say a word or two - or a hundred if a hundred were needed to save a soul? What did he know of heaven and hell? And yet even an old priest buried in a nameless town knew who had deserved heaven. He knew the roll. He began to run through the list of saints in the Catholic pantheon, beginning with the saints for each day of the calendar: "Saint Nunilona, virgin and martyr; Anercio, bishop; Saints Salome, widow, and Alodia-or-Elodia and Nulina, virgins; Cordula and Donate." And on down the line. He was drifting off to sleep when he sat up straight in his bed. "Here I am reciting the saints as if I were counting sheep."

He went outside and looked at the sky. It was raining stars. He was sorry, because he would rather have seen a tranquil sky. He heard roosters crowing. He felt the mantle of night covering the earth. The earth, "this vale of tears."

You're lucky, son. Very lucky," Eduviges Dyada told me.

It was very late by now. The lamp in the corner was beginning to grow dim; it flickered and went out.

I sensed that the woman rose, and I supposed she was leaving to get another lamp. I listened to her receding footsteps. I sat there, waiting.

After a while, when I realized that she was not coming back, I got up, too. I inched my way forward, groping in the darkness, until I reached my room. I lay down on the floor to wait for sleep to come.

I slept fitfully.

It was during one of those intervals that I heard the cry. It was a drawn-out cry, like the howl of a drunk. "Ay-y-y-y, life! I am too good for you!"

I sat bolt upright because it had sounded almost in my ear. It could have been in the street, but I had heard it here, sticking to the walls of my room. When I awoke, everything was silent: nothing but the sound of moths working and the murmur of silence.

No, there was no way to judge the depth of the silence that followed that scream. It was as if the earth existed in a vacuum. No sound: not even of my breathing or the beating of my heart.

As if the very sound of consciousness had been stilled. And just when the pause ended and I was regaining my calm, the cry was repeated; I heard it for a long, long while. "You owe me something, even if it's nothing more than a hanged man's right to a last word."

Then the door was flung open.

"Is that you, dona Eduviges?" I called. "What's going on? Were you afraid?

"My name isn't Eduviges. I am Damiana. I heard you were here and I've come to see you. I want you to come sleep at my house. You'll be able to get rest there."

“Damiana Cisnero”? Aren't you one of the women who lived at the Media Luna?"

"I do live there. That's why it took me so long to get here."

"My mother told me about a woman named Damiana who looked after me when I was born. Was that you?"

"Yes. I'm the one. I've known you since you first opened your eyes."

"I'll be glad to come. I can't get any rest here because of the yelling. Didn't you hear it? How they were murdering someone? Didn't you hear it just now?"

"It may be some echo trapped in here. A long time ago they hanged Toribio Aldrete in this room. Then they locked the door and left him to turn to leather. So he would never find rest. I don't know how you got in, when there isn't any key to open this door."

"It was dona Eduviges who opened it. She told me it was the only room she had available."

"Eduviges Dyada?"

"Yes, she was the one."

"Poor Eduviges. That must mean she's still wandering like a lost soul."

Fulgor Sedano, fifty-four years of age, bachelor, administrator by profession and skilled in filing and prosecuting lawsuits, by the power invested in me and by my own authority, do claim and allege the following . . . " That was what he had written when he filed the complaint against deeds committed by Toribio Aldrete. And he had ended: "The charge is falsifying boundaries."

"There's no one can call you less than a man, don Fulgor. I know you can hold your own.

And not because of the power behind you, but on your own account."

He remembered. That was the first thing Aldrete had told him after they began drinking together, reputedly to celebrate the complaint:

"We'll wipe our asses with this paper, you and I, don Fulgor, because that's all it's good for. You know that. In other words, as far as you're concerned, you've done your part and cleared the air. Because you had me worried, which anyone might be. But now I know what it's all about, it makes me laugh. Falsify boundaries? Me? If he's that stupid, your patron should be red in the face."

He remembered. They had been at Eduviges's place. He had even asked her:

"Say, Viges. Can you let me have the corner room?"

"Whatever rooms you want, don Fulgor. If you want, take them all. Are your men going to spend the night?"

"No, I just need one. Don't worry about us, go on to bed. Just leave us the key."

"Well, like I told you, don Fulgor," Toribio Aldrete had said. "There's no one can doubt your manhood, but I'm fuckin' well fed up with that shit-ass son of your patron."

He remembered. It was the last thing he heard with all his wits about him. Later, he had acted like a coward, yelling, "Power behind me, you say? 'Is it right?"

He used the butt of his whip to knock at Pedro Paramo's door. He thought of the first time he had done that, two weeks earlier. He waited, as he had that first time. And again as he had then, he examined the black bow hanging above the door. But he did not comment again: "Well, how about that! They've hung one over the other. The first one's faded now, but the new one shines like silk, even though you can see it's just something they've dyed."

That first time he had waited so long that he'd begun to think maybe no one was home.

He was just leaving when Pedro Paramo finally appeared.

"Come in, my friend."

It was the second time they had met. The first time only he had been aware of the meeting because it was right after little Pedro was born. And this time. You might almost say it was the first time. And here he was being treated like an equal. How about that! Fulgor followed with long strides, slapping his whip against his leg. He'll soon learn that I'm the man who knows what's what. He'll learn. And know why I've come.

"Sit down, Fulgor. We can speak at our ease here."

They were in the horse corral. Pedro Paramo made himself comfortable on a feed trough, and waited.

"Don't you want to sit down?"

"I prefer to stand, Pedro."

"As you like. But don't forget the don."

Who did the boy think he was to speak to him like that? Not even his father, don Lucas Paramo, had dared do that. So the very first thing, this kid, who had never stepped foot on the Media Luna or done a lick of work, was talking to him as if he were a hired hand. How about that!

"So, what shape is this operation in?"

Sedano felt this was his opportunity. "Now it's my turn," he thought.

"Not so good. There's nothing left. We've sold off the last head of cattle."

He began taking out papers to show Pedro Paramo how much he owed. And he was just ready to

say, "We owe such and such," when he heard the boy ask:

"Who do we owe it to? I'm not interested in how much, just who to."

Fulgor ran down the list of names. And ended: "There's nowhere to get the money to pay. That's the crux of the problem."

"Why not?"

"Because your family ate it all up. They borrowed and borrowed without ever returning any of it. One day you have to pay the piper. I always used to say, 'One of these days they're going to have everything there is.' Well, that's what happened. Now, I know someone who might be interested in buying the land. They'll pay a good price. It will cover your outstanding debts, with a little left over. Though not very much."

"That 'someone' wouldn't be you?"

"What makes you think it's me?"

"I'm suspicious of my own shadow. Tomorrow morning we'll begin to set our affairs in order. We'll begin with the Preciado women. You say it's them we owe the most?"

"Yes. And them we've paid the least. Your father always left the Preciados to the last. I understand that one of the girls, Matilde, went to live in the city. I don't know whether it was Guadalajara or Colima. And that Lola, that is, dona Dolores, has been left in charge of everything. You know, of don Enmedio's ranch. She's the one we have to pay."

"Then tomorrow I want you to go and ask for Lola's hand."

"What makes you think she'd have me? I'm an old man."

"You'll ask her for me. After all, she's not without her charms. Tell her I'm very much in love with her. Ask her if she likes the idea. And on the way, ask Father Renteria to make the arrangements. How much money can you get together?"

"Not a centavo, don Pedro."

"Well, promise him something. Tell him the minute I have any money, I'll pay him. I'm pretty sure he won't stand in the way. Do it tomorrow. Early."

"And what about Aldrete?

"What does Aldrete have to do with anything? You told me about the Preciado women, and the Fregosos and the Guzmans. So what's this about Aldrete?"

"It's the matter of the boundaries. He's been putting up fences, and now he wants us to put up the last part in order to establish the property lines."

Pedro Paramo

Pedro Paramo