- Home

- Rulfo, Juan

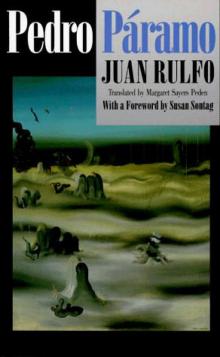

Pedro Paramo Page 7

Pedro Paramo Read online

Page 7

"What do you mean? That I must look somewhere else if I want to confess?"

"Yes, you must. You cannot continue to consecrate others when you yourself are in sin."

"But what if they remove me from my ministry?"

"Maybe you deserve it. They will be the ones to judge."

"Couldn't you . . . ? Provisionally, I mean. . . . I must administer the last rites . . . give communion. So many are dying in my village, Father."

"Oh, my friend, let God judge the dead."

"Then you won't absolve me?"

And the priest in Contla had told him no.

Later the two of them had strolled through the azalea-shaded cloister of the parish patio. They sat beneath an arbor where grapes were ripening.

"They're bitter, Father," the priest anticipated Father Renteria's question. "We live in a land in which everything grows, thanks to God's providence; but everything that grows is bitter. That is our curse."

"You're right, Father. I've tried to grow grapes over in Comala. They don't bear. Only guavas and oranges: bitter oranges and bitter guavas. I've forgotten the taste of sweet fruit.

Do you remember the China guavas we had in the seminary? The peaches? The tangerines that shed their skin at a touch? I brought seeds here. A few, just a small pouch. Afterward, I felt it would have been better to leave them where they were, since I only brought them here to die."

"And yet, Father, they say that the earth of Comala is good. What a shame the land is all in the hands of one man. Pedro Paramo is still the owner, isn't he?"

"That is God's will."

"I can't believe that the will of God has anything to do with it. You don't believe that, do you, Father?"

"At times I have doubted; but they believe it in Comala."

"And are you among the 'they'?"

"I am just a man prepared to humble himself, now while he has the impulse to do so."

Later, when they said their good-byes, Father Renteria had taken the priest's hands and kissed them. Now that he was home, and returned to reality, he did not want to think about the morning in Contla.

He rose from the bench and walked to the door.

"Where are you going, Uncle?"

His niece Ana, always present, always by his side, as if she sought his shadow to protect her from life.

"I'm going out to walk for a while, Ana. To blow off steam."

"Do you feel sick?"

"Not sick, Ana. Bad. I feel that's what I am. A bad man."

He walked to the Media Luna and offered his condolences to Pedro Paramo. Again he listened to his excuses for the charges made against his son. He let Pedro Paramo talk. None of it mattered, after all. On the other hand, he did decline his invitation to eat.

"I can't do that, don Pedro. I have to be at the church early because a long line of women are already waiting at the confessional. Another time."

He walked home, then toward evening went directly to the church, just as he was, bathed in dust and misery. He sat down to hear confessions.

The first woman in line/was old Dorotea, jMio was always waiting for the church d He smelled the odor of alcohol.

"What? Now you're drinking? How long have you been doing this?"

"I went to Miguelito's wake, padre. And I overdid it a little. They gave me so much to drink that I ended up acting like a clown."

"That's all you've ever done, Dorotea."

"But now I've come with my sins, padre. Sins to spare."

On many occasions he had told her, "Don't bother to confess, Dorotea; you'd be wasting my time. You couldn't commit a sin anymore, even if you tried. Leave that to others."

"I have now, padre. It's the truth."

"Tell me."

"Since it can't do him any harm now, I can tell you that I'm the one who used to get the girls for the deceased. For Miguelito Paramo."

Father Renteria, stalling for time to think, seemed to emerge from his fog as he asked, almost from habit:

"For how long?"

"Ever since he was a boy. From that time he had the measles."

"Repeat to me what you just said, Dorotea."

"Well, that I was the one who rounded up Miguelito's girls."

"You took them to him?"

"Sometimes I did. Other times I just made the arrangements. And with some, all I did was head him in the right direction. You know, the hour when they would be alone, and when he could catch them unawares."

"Were there many?"

He hadn't meant to ask, but the question came out by force of habit.

"I've lost count. Lots and lots."

"What do you think I should do with you, Dorotea? You be the judge. Can you pardon what you've done?"

"I can't, padre. But you can. That's why I'm here."

"How many times have you come to ask me to send you to Heaven when you die? You hoped to find your son there, didn't you, Dorotea? Well, you won't go to Heaven now. May God forgive you."

"Thank you, padre."

"Yes. And I forgive you in His name. You may go."

"Aren't you going to give me any penance?"

"You don't need it, Dorotea."

"Thank you, padre."

"Go with God."

He rapped on the window of the confessional to summon another of the women. And while he listened to "I have sinned," his head slumped forward as if he could no longer hold it up. Then came the dizzyness, the confusion, the slipping away as if in syrupy water, the whirling lights; the brilliance of the dying day was splintering into shards. And there was the taste of blood on his tongue. The "I have sinned" grew louder, was repeated again and again: "for now and forever more," "for now and forever more," "for now . . ."

"Quiet, woman," he said. "When did you last confess?"

"Two days ago, padre."

Yet she was back again. It was as if he were surrounded by misfortune. What are you doing here, he asked himself. Rest. Go rest. You are very tired.

He left the confessional and went straight to the sacristy. Without a glance for the people waiting, he said:

"Any of you who feel you are without sin may take Holy Communion tomorrow."

Behind him, as he left, he heard the murmuring.

I am lying in the same bed where my mother died so long ago; on the same mattress, beneath the same black wool coverlet she wrapped us in to sleep. I slept beside her, her little girl, in the special place she made for me in her arms.

I think I can still feel the calm rhythm of her breathing; the palpitations and sighs that soothed my sleep. . . . I think I feel the pain of her death. . . . But that isn't true.

Here I lie, flat on my back, hoping to forget my loneliness by remembering those times.

Because I am not here just for a while. And I am not in my mother's bed but in a black box like the ones for burying the dead. Because I am dead.

I sense where I am, but I can think. . . .

I think about the limes ripening. About the February wind that used to snap the fern stalks before they dried up from neglect. The ripe limes that filled the overgrown patio with their fragrance.

The wind blew down from the mountains on February mornings. And the clouds

gathered there waiting for the warm weather that would force them down into the valley.

Meanwhile the sky was blue, and the light played on little whirlwinds sweeping across the earth, swirling the dust and lashing the branches of the orange trees.

The sparrows were twittering; they pecked at the wind-blown leaves, and twittered.

They left their feathers among the thorny branches, and chased the butterflies, and twittered. It was that season.

February, when the mornings are filled with wind and sparrows and blue light. I remember. That is when my mother died.

I should have wailed. I should have wrung my hands until they were bleeding. That is how you would have wanted it. But in fact, wasn't that a joyful morning? The breeze was blowing in through the open door, tearing loose the ivy tendrils. Ha

ir was beginning to grow on the mound between my legs, and my hands trembled hotly when I touched my breasts. Sparrows were playing. Wheat was swaying on the hillside. I was sad that she would never again see the wind playing in the jasmines; that her eyes were closed to the bright sunlight. But why should I weep?

Do you remember, Justina? You arranged chairs in a row in the corridor where the people who came to visit could wait their turn. They stood empty. My mother lay alone amid the candles; her face pale, her white teeth barely visible between purple lips frozen by the livid cold of death.

Her eyelashes lay still; her heart was still. You and I prayed interminable prayers she could not hear, that you and I could not hear above the roar of the wind in the night. You ironed her black dress, starched her collar and the cuffs of her sleeves so her hands would look young crossed upon her dead breast - her exhausted, loving breast that had once fed me, that had cradled me and throbbed as she crooned me to sleep.

No one came to visit her. Better that way. Death is not to be parceled out as if it were a blessing. No one goes looking for sorrow.

Someone banged the door knocker. You went to the door.

"You go," I said. "I see people through a haze. Tell them to go away. Have they come for money for the Gregorian masses? She didn't leave any money. Tell them that, Justina. Will she have to stay in purgatory if they don't say those masses? Who are they to mete out justice, Justina? You think I'm crazy? That's fine."

And your chairs stood empty until we went to bury her, accompanied by the men we had hired, sweating under a stranger's weight, alien to our grief. They shoveled damp sand into the grave; they lowered the coffin, slowly, with the patience of their office, in the breeze that cooled them after their labors. Their eyes cold, indifferent. They said: "It'll be so much." And you paid them, the way you might buy something at the market, untying the corner of the tear-soaked handkerchief you'd wrung out again and again, the one that now contained the money for the burial. . . .

And when they had gone away, you knelt on the spot above her face and you kissed the ground, and you would have dug down toward her if I hadn't said: "Let's go, Justina. She isn't here now. There's nothing here but a dead body."

“That you talking, Dorotea?"

"Who, me? I was asleep for a while. Are you still afraid?"

"I heard someone talking. A woman's voice. I thought it was you."

"A woman's voice? You thought it was me? It must be that woman who talks to herself.

The one in the large tomb. Dona Susanita. She's buried close to us. The damp must have got to her, and she's moving around in her sleep."

"Who is she?"

"Pedro Paramo's last wife. Some say she was crazy. Some say not. The truth is that she talked to herself even when she was alive."

"She must have died a long time ago."

"Oh, yes! A long time ago. What did you hear her say?"

"Something about her mother."

"But she didn't have a mother. . . . "

"Well, it was her mother she was talking about."

"Hmmm. At least, her mother wasn't with her when she came. Wait a minute. I remember now the mother was born here, and when she was getting along in years, they vanished. Yes, that's it. Her mother died of consumption. She was a strange woman who was always sick and never visited with anyone."

"That's what she was saying. That no one had come to visit her mother when she died."

"What did she mean? No wonder no one wanted to step inside her door, they were afraid of catching her disease. I wonder if the Indian woman remembers?"

"She was talking about that."

"When you hear her again, let me know. I'd like to know what she's saying."

"You hear? I think she's about to say something. I hear a kind of murmuring."

"No, that isn't her. That's farther away and in the other direction. And that's a man's voice. What happens with these corpses that have been dead a long time is that when the damp reaches them they begin to stir. They wake up."

"The heavens are bountiful. God was with me that night. If not, who knows what might have happened. Because it was already night when I came to. . . . "

"You hear it better now?"

"Yes."

". . .I was covered with blood. And when I tried to get up my hands slipped in the puddles of blood in the rocks. It was my blood. Buckets of blood. But I wasn't dead. I knew that. I knew that don Pedro hadn't meant to kill me. Just give me a scare. He wanted to find out whether I'd been in Vilmayo that day two years before. On San Cristobal's day.

At the wedding. What wedding? Which San Cristobal's? There I was slipping around in my own blood, and I asked him just that: 'What wedding, don Pedro? No! No, don Pedro. I wasn't there. I may have been near there, but only by chance. . . .' He never meant to kill me.

He left me lame — you can see that - and, sorry to say, without the use of my arm. But he didn't kill me. They say that ever since then I've had one wild eye. From the scare. I tell you, though, it made me more of a man. The heavens are bountiful. And don't you ever doubt it."

"Who was that?"

"How should I know? Any one of dozens. Pedro Paramo slaughtered so many folks after his father was murdered that he killed nearly everybody who attended that wedding. Don Lucas Paramo was supposed to give the bride away. And it was really by accident that he died, because it was the bridegroom someone had a grudge against. And since they never found out who fired the bullet that struck him down, Pedro Paramo wiped out the lot. It happened over there on Vilmayo ridge, where there used to be some houses you can't find any trace of now. . . .Listen. . . .Now that sounds like her. Your ears are younger.

You listen. And then tell me what she says."

"I can't understand a thing. I don't think she's talking; just moaning."

"What's she moaning about?"

"Well, who knows."

"It must be about something. No one moans just to be moaning. Try harder."

"She's moaning. Just moaning. Maybe Pedro Paramo made her suffer."

"Don't you believe it. He loved her. I'm here to tell you that he never loved a woman like he loved that one. By the time they brought her to him, she was already suffering — maybe crazy. He loved her so much that after she died he spent the rest of his days slumped in a chair, staring down the road where they'd carried her to holy ground. He lost interest in everything. He let his lands lie fallow, and gave orders for the tools that worked it to be destroyed. Some say it was because he was worn out; others said it was despair. The one sure thing is that he threw everyone off his land and sat himself down in his chair to stare down that road.

"From that day on the fields lay untended. Abandoned. It was a sad thing to see what happened to the land, how plagues took over as soon as it lay idle. For miles around, people fell on hard times. Men packed up and left in search of a better living. I remember days when the only sound in Comala was good-byes; it seemed like a celebration every time we sent someone on his way. They went, you know, with every intention of coming back.

They asked us to keep an eye on their belongings and their families. Later, some sent for their family but not their things. And then they seemed to forget about the village, and about us - and even about their belongings. I stayed because I didn't have anywhere to go.

Some stayed waiting for Pedro Paramo to die, because he'd promised to leave them his land and his goods and they were living on that hope. But the years went by and he lived on, propped up like a scarecrow gazing out across the lands of the Media Luna.

"And not long before he died we had that Cristeros war, and the troops drained off the few men he had left. That was when I really began to starve, and things were never the same again.

"And all of it was don Pedro's doing, because of the turmoil of his soul. Just because his wife, that Susanita, had died. So you tell me whether he loved her."

It was Fulgor Sedano who told him:

"Patron. You know who's back in town?"

"Who?"

"Bartolome San Juan."

"How come?"

"That's what I asked myself. Wonder why he's come back?"

"Haven't you looked into it?"

"No. I wanted to tell you first. He didn't inquire about a house. He went straight to your old place. He got off his horse and moved in his suitcases, just as if you'd already rented it to him. He didn't seem to have any doubts."

"And what are you doing about it, Fulgor? Why haven't you found out what's going on? Isn't that what you're paid to do?"

"I was a little thrown off by what I just told you. But tomorrow I'll find out, if you think we should."

"Never mind about tomorrow. I'll look into the San Juans. Both of them came?"

"Yes. Him and his wife. But how did you know?"

"Wasn't it his daughter?"

"Well, the way he treats her, she seems more like his wife."

"Go home and go to bed, Fulgor."

"With your leave."

I waited thirty years for you to return, Susana. I wanted to have it all. Not just part of it, but everything there was to have, to the point that there would be nothing left for us to want, no desire but your wishes. How many times did I ask your father to come back here to live, telling him I needed him. I even tried deceit.

I offered to make him my administrator, anything, as long as I could see you again. And what did he answer? "No response," the messenger always said. "Senor don Bartolome tears up your letters as soon as I hand them to him." But through that boy I learned that you had married, and before long I learned you were a widow and had gone back to keep your father company.

Then silence.

The messenger came and went, and each time he reported: "I can't find them, don Pedro.

People say they've left Mascota. Some say they went in one direction, and some say another."

I told him: "Don't worry about the expense. Find them. They haven't been swallowed up by the earth."

And then one day he came and told me:

"I've been all through the mountains searching for the place where don Bartolome San Juan might be hiding and at last I found him, a long way from here, holed up in a little hollow in the hills, living in a log hut on the site of the abandoned La Andromeda mines."

Pedro Paramo

Pedro Paramo