- Home

- Rulfo, Juan

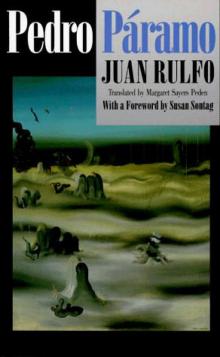

Pedro Paramo Page 8

Pedro Paramo Read online

Page 8

Strange winds were blowing then. There were reports of armed rebellion. We heard rumors. Those were the winds that blew your father back here. Not for his own sake, he wrote in his letter, but your safety. He wanted to bring you back to civilization.

I felt that the heavens were parting. I wanted to run to meet you. To envelop you with happiness. To weep with joy. And weep I did, Susana, when I learned that at last you would return.

Some villages have the smell of misfortune. You know them after one whiff of their stagnant air, stale and thin like everything old. This is one of those villages, Susana.

"Back there, where we just came from, at least you could enjoy watching things being born: clouds and birds and moss. You remember? Here there's nothing but that sour, yellowish odor that seems to seep up from the ground. This town is cursed, suffocated in misfortune.

"He wanted us to come back. He's given us his house. He's given us everything we need.

But we don't have to be grateful to him. This is no blessing for us, because our salvation is not to be found here. I feel it.

"Do you know what Pedro Paramo wants? I never imagined that he was giving us all this for nothing. I was ready to give him the benefit of my toil, since we had to repay him somehow. I gave him all the details about La Andromeda, and convinced him that the mine had promise if we worked it methodically. You know what he said? 'I'm not interested in your mine, Bartolome San Juan. The only thing of yours I want is your daughter. She's your crowning achievement.'

"He loves you, Susana. He says you used to play together when you were children. That he knows you. That you used to swim together in the river when you were young. I didn't know that. If I'd known I would have beat you senseless."

"I'm sure you would."

"Did I hear what you said? 'I'm sure you would'?"

"You heard me."

"So you're prepared to go to bed with him?"

"Yes, Bartolome."

"Don't you know that he's married, and that he's had more women than you can count?"

"Yes, Bartolome."

"And don't call me Bartolome! I'm your father!"

Bartolome San Juan, a dead miner. Susana San Juan, daughter of a miner killed in the Andromeda mines. He saw it clearly. "I must go there to die," he thought. Then he said: "I've told him that although you're a widow, you are still living with your husband - or at least you act as if you are. I've tried to discourage him, but his gaze grows hard when I talk to him, and as soon as I mention your name, he closes his eyes. He is, I haven't a doubt of it, unmitigated evil. That's who Pedro Paramo is."

"And who am I?"

"You are my daughter. Mine. The daughter of Bartolome San Juan."

Ideas began to form in Susana San Juan's mind, slowly at first; they retreated and then raced so fast she could only say:

"It isn't true. It isn't true."

"This world presses in on us from every side; it scatters fistfuls of our dust across the land and takes bits and pieces of us as if to water the earth with our blood. What did we do? Why have our souls rotted away? Your mother always said that at the very least we could count on God's mercy. Yet you deny it, Susana. Why do you deny me as your father? Are you mad?"

"Didn't you know?"

"Are you mad?"

"Of course I am, Bartolome. Didn't you know?"

You know of course, Fulgor, that she is the most beautiful woman on the face of the earth. I had come to believe I had lost her forever. I don't want to lose her again. You understand me, Fulgor? You tell her father to go explore his mines. And there . . . I imagine it wouldn't be too hard for an old man to disappear in a territory where no one ever ventures. Don't you agree?"

"Maybe so."

"We need it to be so. She must be left without family. We're called on to look after those in need. You agree with that, don't you?"

"I don't see any difficulty with that."

"Then get about it, Fulgor. Get on with it."

"And what if she finds out?"

"Who's going to tell her? Let's see, tell me. Just between the two of us, who's going to tell her?"

"No one, I guess."

"Forget the 'I guess.' Forget that as of now, and everything'll work out fine. Remember how much needs to be done at the Andromeda. Send the old man there to keep at it. To come and go as he pleases. But don't let him get the idea of taking his daughter. We'll look after her here. His work is there in the mines and his house is here anytime he wants it.

Tell him that, Fulgor."

"I'd like to say once more that I like the way you do things, patron. You seem to be getting your spirit back."

Rain is falling on the fields of the valley of Comala. A fine rain, rare in these lands that know only downpours. It is Sunday. The Indians have come down from Apango with their rosaries of I chamomile, their rosemary, their bunches of thyme. They have come without ocote pine, because the wood is wet, and without oak mulch, because it, too, is wet from the long rain. They spread their herbs on the ground beneath the arches of the arcade. And wait.

The rain falls steadily, stippling the puddles.

Rivers of water course among the furrows where the young maize is sprouting. The men have not come to the market today; they are busy breaching the rows so the water will find new channels and not carry off the young crop. They move in groups, navigating the flooded fields beneath the rain, breaking up soft clumps of soil with their spades, firming the shoots with their hands, trying to protect them so they will grow strong.

The Indians wait. They feel this is a ill-fated day. That may be why they are trembling beneath their soaking wet gabanes, their straw capes - not from cold, but fear. They stare at the fine rain and at the sky hoarding its clouds.

No one comes. The village seems uninhabited. A woman asks for a length of darning cotton, and a packet of sugar, and, if it is to be had, a sieve for straining cornmeal gruel. As the morning passes, the gabanes grow heavy with moisture. The Indians talk among themselves, they tell jokes, and laugh. The chamomile leaves glisten with a misting of rain. They think, "If only we'd brought a little pulque, it wouldn't matter; but the hearts of the magueys are swimming in a sea-of-water. Well, what can you do?"

Beneath her umbrella, Justina Diaz makes her way down the straight road leading from the Media Luna, avoiding the streams of water gushing onto the sidewalks. As she passed the main entrance to the church, she made the sign of the cross. She walked beneath the arches into the plaza. All the Indians turned to watch her. She felt their eyes upon her, as if she were under intense scrutiny. She stopped at the first display of herbs, bought ten centavos worth of rosemary, and then retraced her steps, followed by countless pairs of Indian eyes.

"Everything costs so much this time of year," she thought as she walked back toward the Media Luna. "This pitiful little bunch of rosemary for ten centavos. It's barely enough to give off a scent."

Toward dusk the Indians rolled up their wares. They walked into the rain with their heavy packs on their backs. They stopped by the church to pray to the Virgin, leaving a bunch of thyme as an offering. Then they set off toward Apango, on their way home.

"Another day," they said. And they walked down the road telling jokes, and laughing.

Justina Diaz went into Susana San Juan's bedroom and set the rosemary on a small shelf. The closed curtains blocked out the light, so that she saw only shadows in the darkness; she merely guessed at what she was seeing. She supposed that Susana San Juan was asleep; she wished that she did nothing but sleep, and as she was sleeping now, Justina was content. But then she heard a sigh that seemed to come from a far corner of the darkened room.

"Justina!" someone called.

She looked around. She couldn't see anyone but she felt a hand on her shoulder and a breath against her ear. A secretive voice said, "Go-away, Justina. Bundle up your things, and leave. We don't need you anymore."

"She needs me," she replied, standing straighter. "She's sick, and she needs me."

"No

t anymore, Justina. I will stay here and take care of her."

"Is that you, don Bartolome?" But she did not wait for the answer. She screamed a scream that reached the ears of men and women returning from the fields, a cry that caused them to say "That sounded like someone screaming, but it can't be human."

The rain deadens sounds. It can be heard when all other sound is stilled, flinging its icy drops, spinning the thread of life.

"What's the matter, Justina? Why did you scream?" Susana San Juan asked.

"I didn't scream, Susana. You must have been dreaming."

"I've told you, I never dream. You have no consideration. I scarcely slept a wink. You didn't put the cat out last night, and it kept me awake."

"It slept with me, between my legs. It got wet, and I felt sorry for it and let it stay in my bed; but it didn't make any noise."

"No, it didn't make any noise. But it spent the night like a circus cat, leaping from my feet to my head, and meowing softly as if it were hungry."

"I fed it well, and it never left my bed all night. You've been dreaming lies again, Susana."

"I tell you, it kept startling me all night with its leaping about. Your cat may be very affectionate, but I don't want it around when I'm sleeping."

"You're seeing things, Susana. That's what it is. When Pedro Paramo comes, I'm going to tell him that I can't put up with you any longer. I'll tell him I'm leaving. There are plenty of nice people who will give me work. Not all of them are crazy like you, or enjoy humiliating a person the way you do. Tomorrow morning I'm leaving; I'll take my cat and leave you in peace."

"You won't leave, you perverse and wicked Justina. You're not going anywhere, because you will never find anyone who loves you the way I do."

"No, I won't leave, Susana. I won't leave. You know I will take care of you. Even though you make me swear I won't, I will always take care of you."

She had cared for Susana from the day she was born. She had held her in her arms. She had taught her to walk. To take those first steps that seemed eternal. She had watched her lips and eyes grow sweet as sugar candy. "Mint candy is blue. Yellow and blue. Green and blue. Stirred with spearmint and wintergreen." She nibbled at her chubby legs. She entertained her by offering her a breast to nurse that had no milk, that was only a toy. "Play with this," she told Susana. "Play with your own little toy." She could have hugged her to pieces.

Outside, rain was falling on the banana leaves and water in the puddles sounded as if it were boiling.

The sheets were cold and damp. The drainpipes gurgled and foamed, weary of laboring day and night, day and night. Water kept pouring down, streaming in diluvial burbling.

It was midnight; outside, the sound of the rain blotted out all other sounds.

Susana San Juan woke early. She sat up slowly, then got out of bed. Again she felt the weight in her feet, a heaviness rising up her body, trying to reach her head:

"Is that you, Bartolome?'

She thought she heard the door squeak, as if someone were entering or leaving. And then only the rain, intermittent, cold, rolling down the banana leaves, boiling in its own ferment.

She slept again and did not wake until light was falling on red bricks beaded with moisture in the gray dawn of a new day. She called: "Justina!"

Justina, throwing a shawl around her shoulders, appeared immediately, as if she had been right outside the door.

"What is is, Susana?"

"The cat. The cat's in here again."

"My poor Susana."

She laid her head on Susana's breast and hugged her until Susana lifted her head and asked "Why are you crying? I'll tell Pedro Paramo how good you are to me. I won't tell him anything about how your cat frightens me. Don't cry, Justina."

"Your father's dead, Susana. He died night before last. They came today to say there's nothing we can do; they've already buried him. It was too far to bring his body back here.

You're all alone now, Susana."

"Then it was Father," Susana smiled. "So he came to tell me good-bye," she said. And smiled.

Many years earlier, when she was just a little girl, he had said one day:

"Climb down, Susana, and tell me what you see."

She was dangling from a rope that cut into her waist and rubbed her hands raw, but she didn't want to let go. That rope was the single thread connecting her to the outside world.

"I don't see anything, papa."

"Look hard, Susana. See if you don't see something."

And he shone the lamp on her.

"I don't see anything, papa."

"I'll lower you a little farther. Let me know when you're on the bottom."

She had entered through a small opening in some boards. She had walked over rotted, decaying, splintered planks covered with clayey soil:

"Go a little lower, Susana, and you'll find what I told you."

She bumped lower and lower, swaying in the darkness, with her feet swinging in empty space.

"Lower, Susana. A little lower. Tell me if you see anything."

And when she felt the ground beneath her feet she stood there dumb with fear. The lamplight circled above her and then focused on a spot beside her. The yell from above made her shiver:

"Hand me that, Susana!"

She picked up the skull in both hands, but when the light struck it fully, she dropped it.

"It's a dead man's skull," she said.

"You should find something else there beside it. Hand me whatever's there."

The skeleton broke into individual bones: the jawbone fell away as if it were sugar. She handed it up to him, piece after piece, down to the toes, which she handed him joint by joint. The skull had been first, the round ball that had disintegrated in her hands.

"Keep looking, Susana. For money. Round gold coins. Look everywhere, Susana."

And then she did not remember anything, until days later she came to in the ice: in the ice of her father's glare.

That was why she was laughing now.

"I knew it was you, Bartolome."

And poor Justina, weeping on Susana's bosom, sat up to see what she was laughing about, and why her laughter had turned to wild guffaws.

Outside, it was still raining. The Indians had gone. It was Monday and the valley of Comala was drowning in rain.

The winds continued to blow, day after day. The winds that had brought the rain. The rain was over but the wind remained. There in the fields, tender leaves, dry now, lay flat against the furrows, escaping the wind. By day the wind was bearable; it worried the ivy and rattled the roof tiles; but by night it moaned, it moaned without ceasing. Canopies of clouds swept silently across the sky, so low they seemed to scrape the earth.

Susana San Juan heard the wind lashing against the closed window. She was lying with her arms crossed behind her head, thinking, listening to the night noises: how the night was buffeted by bursts of restless wind. Then the abrupt cessation.

Someone has opened the door. A rush of air blows out the lamp. She sees only darkness, and conscious thought is suspended. She hears faint rustlings. The next moment she hears the erratic beating of her heart. Through closed eyelids she senses the flame of light.

She does not open her eyes. Her hair spills across her face. The light fires drops of sweat on her upper lip. She asks: "Is that you, Father?"

"Yes, I am your father, my child."

She peers through half-closed eyelids. Her hair seems to be cloaking a shadowy figure on the ceiling, its head looming above her face. Through the haze of her eyelashes a blurred figure takes form. A diffuse light burns in the place of its heart, a tiny heart pulsing like a flickering flame. "Your heart is dying of pain," Susana thinks. "I know that you've come to tell me Florencio is dead, but I already know that. Don't be sad about anything else; don't worry about me. I keep my grief hidden in a safe place. Don't let your heart go out!"

She got out of bed and dragged herself toward Father Renteria.

"Let me console you," he said, prot

ecting the flame of the candle with his cupped hand, "console you with my own inconsolable sorrow."

Father Renteria watched as she approached him and encircled the lighted flame with her hands, and then she lowered her face to the burning wick until the smell of burning flesh forced him to jerk the candle away and blow out the flame.

Again in darkness, Susana ran to hide beneath the sheets.

Father Renteria said:

"I have come to comfort you, daughter."

"Then you may go, Father," she replied. "Don't come back. I don't need you."

And she listened to the retreating footsteps that had always left a sensation of cold and fear.

"Why do you come see me, when you are dead?"

Father Renteria closed the door and stepped out into the night air.

The wind continued to blow.

A man they called El Tartamudo came to the Media Luna and asked for Pedro Paramo.

"Why do you want to see him?"

"I want to t-talk with him."

"He isn't here."

"T-tell him, when he comes back, that it's about d-don Fulgor."

"I'll go look for him, but you may have to wait a while."

"T-tell him it's uh-urgent."

"I'll tell him."

El Tartamudo waited, without dismounting from his horse. After a while Pedro Paramo, whom El Tartamudo had never seen, came up and asked:

"What can I do for you?"

"I need to t-talk directly to the patron."

"I am the patron. What do you want?"

"W-well. Just this. They've m-murdered don Fulgor Sedano. I was w-with him. We'd ridden down to the spillways to find out whuh-why the water had dried up. And wh-while we were doing that a band of m-men came riding toward us. And o-one of them yelled 'I n-know him. He's the foreman of the M-Media Luna.'

"Th-they ignored me. But they t-told don Fulgor to get off his horse. They s-said they were r-revolutionaries. And th-that they wanted your land. T-take off!' they told don Fulgor. "R-run tell your patron to be expecting us!' And he st-started off, sc-scared as hell.

N-not too fast, because he's so fat; but he ran. They sh-shot him as he ran. He d-d-died with one foot in the air and one on the g-ground.

Pedro Paramo

Pedro Paramo